- Home

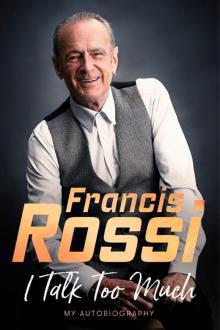

- Francis Rossi

I Talk Too Much Page 3

I Talk Too Much Read online

Page 3

Another instrumental that always sent me into a deep swoon was Acker Bilk’s ‘Stranger on the Shore’. Sweet Jesus, as my dad would say … that sultry quivering clarinet, those seashore strings. If that came on the radio on a Sunday morning as we sat there having sausages and bacon, we would fall into a collective blush, our emotions all spooned-out and stirred slowly in front of us on the table. None of us would speak, just all plugged into the same good feeling.

Then came the Beatles and everything – everything – changed overnight. Not just music, but literally everything. Unless you lived through it you simply cannot comprehend what a big change to the world it was when the Beatles came along. It was the start of the sixties, the start of a whole new post-war world. They were on the side of the angels yet they had better tunes even than the devil. No musician alive before or after the Beatles hasn’t been enormously affected by them.

In terms of learning to play an instrument, I’d messed around on a harmonica when I was about four years old. Then I had a little Hohner Mignon accordion, those Italian ones you see with what looks like a piano keyboard down one side. But you had to have lessons to learn that and I didn’t have the patience at that age. I wanted to be out in the garden playing with my brother and my cousins. The TV was pretty rubbish back then – only two channels, which no one in our house watched anyway because they were so busy working all the time.

All this somehow went into my thinking about music too. I desperately wanted to learn the guitar but from the word go the only real way I ever had of measuring success would be in how popular what I did was. I wanted to get good but it wouldn’t mean anything if nobody liked it. All performers are like this if they are honest. The minute you put yourself on a stage and try and sell tickets for people to come and watch you, that’s how you really measure success – by how many people actually pay to see you. I always wanted to know how many people were coming to a show. How many records a certain song had sold. And how did that compare to other songs? Other crowds? My dad and his family always talked about ‘turnover’ and that’s exactly how I’ve always measured success. By how many tickets we’ve sold, how many records. How many ‘pieces’.

I imagine some people reading that and thinking I only got into music for the money. Well, that was not the only reason. But I definitely saw it as a means to an end. I was either going to make it as a musician or start driving an ice-cream van. It would have been easier to simply become part of the family business. But I chose the hard way. Learn to play an instrument, try and find a band. Then play every shithole that will have you until something big happens – or doesn’t. As is the case for most people that are crazy enough to decide to try and do something in music.

The thing that’s harder to explain is where my musical influences came from. It was the Everly Brothers that got me dreaming of playing guitar and making music with my own brother. Dominic was a couple of years younger than me and therefore completely under my command in those first tender years. Or so I liked to think. In fact, my dear brother was already his own man; he was just much nicer than me and therefore quite happy for me to make grand plans for us both, knowing full well he wasn’t going to pay the slightest bit of attention when the time actually came for action.

For example, I’d convinced myself that Dominic and I could be like the English answer to the Everly Brothers, and so we both agreed to ask for guitars for Christmas when I was nine. I pictured us sitting there trying to sing and strum along together. But Dominic got cold feet at the last moment and asked for a train set instead. Which actually worked out fine in the end – he became an accountant. My accountant. Cheers, Dom! That is, until he decided he didn’t like the way the music business works. In fact, Dominic was very much the opposite of me in some ways. I was high-strung and nervous and always looking for the angle. He was quieter, calmer, more trusting and giving in many ways. Like I say, he was simply nicer. It didn’t always work to his advantage, like when Dom and I were adults and my mum went completely bonkers religious. I was married and the band was starting to work all the time, so I couldn’t have been there as much even if I’d wanted to. Dominic would stick with her, give in to her mad choices, hold her hand and tell her reassuring things. I wasn’t having any of it. I was off, out the door, again, too busy following my own nutty dreams to want to be held back by her. Dom, he hung on in there, bless him.

Whoever we were, or thought we were, or would one day be, my parents let us boys get on with it. They didn’t fall over themselves to push us in any particular direction, but they were quite supportive in a quiet sort of way. That helped me much more than I realised at the time. It gave me the impetus to keep going. Otherwise I might have abandoned the guitar completely. But even when Dominic decided his train set was more fun, I find it interesting that years later in Status Quo I would develop this guitar-singing ‘brother’ relationship with Rick Parfitt. That was absolutely not a conscious thing for me, but I look back now and I see it all too clearly. I also see the influence of Everly hits like ‘Wake Up Little Susie’ and ‘Bye Bye Love’. Those big strumming chords are right there in Quo hits like ‘Caroline’ and ‘Down Down’. The way the vocals blend for me and Rick until they sound almost like one voice is also pure Everly Brothers.

What’s far less obvious though are the other, much deeper musical influences that I now realise were at play. For example, an old Italian novelty song called ‘Poppa Piccolino’. This was done by loads of different singers, from Petula Clark to Diana Decker and even the Billy Cotton Orchestra. The first time I heard it was when my mum played it for me to cheer me up after I’d fallen down the stairs again. I always used to say I loved that song so much not just because it was so jolly and catchy but because of the fuss my mother was making over me at the time. I used to joke that I enjoyed the attention so much I threw myself down the stairs again the next day. Only she figured out my game and threatened to throw me down the stairs herself if I didn’t stop pestering her.

The record stayed with me though – and for far longer than I imagined. Until one day I realised how much the Quo sound had to do with that Italian shuffle beat that ‘Poppa Piccolino’ had. That very kind of singsong ta-da-de-dah beat. If you listen it’s in nearly all the biggest Quo hits. I had assumed it came from my fascination for blues-influenced British sixties bands that used that brush-and-pan shuffle too. It was at the heart of my love of American country music as well – which, if you want to get really deep here, is derived from traditional Irish music. Hello Mum!

Whatever the origins – and like most music, I suspect it can be found around the world – the fact was I fell in love with that shuffle rhythm. You could say it’s in my blood.

When I was eleven, I joined the school orchestra. Not as a guitarist but as a trumpet player. That was when I first met Alan Lancaster, who I would go on to form Status Quo with, and another kid named Alan Key, a laidback boy who played the trumpet like I did. Lancaster played the trombone.

Alan Lancaster was a short-arse, but he was the guvnor. He made that clear from the off. Always had plenty to say for himself. A born leader, you might say. I quickly became a follower. I was strong on the outside, but Alan was the real deal. He probably saw the group as his group, and no one was about to argue with him. He was known to be handy with his fists, put it that way. Eventually, as my confidence grew, I would challenge him. Remind him that no one was the leader of the group; that we were all in it together. But Alan wasn’t the kind of bloke to back down in an argument and we ended up having a lot of rows about it. It didn’t change a thing. Alan never backed down about anything. That said, democracy in a group never works. You have to have leaders or the whole thing just never goes anywhere.

Early on, though, that suited me because I was not your typical alpha male. Having Alan as your schoolmate meant you were safe from all the other hooligans, the ones who told me I had a girl’s name in Francis and that I spoke funny. Even Alan, when I first met him, told me: ‘You talk fucking poncey

like, doncha?’ But I started hanging out more and more at his house. I loved his mum and dad. That expression: salt of the earth? Alan Lancaster’s mum and dad really were.

Alan’s mum, May, was an absolutely lovely and decent woman. I always assumed she had Spanish blood because she was dark and passionate. She used to make a big fuss of me. His dad, Harry, was really nice to me too. He was an ex-boxer. One of those blokes who used to come home from work every evening, take his shirt off and have a wash at the kitchen sink in his string vest and a shave for the evening. He wouldn’t have a shave for work.

I was there one day waiting for Alan to get ready. His dad said: ‘You’ll wait forever for that boy, you will.’ So we’re watching the telly and there’s some bloke on there who’s reasonably well spoken and Harry calls out: ‘Here, May! Look, it’s like Ross on the telly!’ Ross was what he used to call me. She came in the room, had a look and went, ‘Naw. He’s one of us now.’ I was so proud to think I’d become more like them, more like that working-class south London Jack the Lad. The kind that would frighten the shit out of people. ‘Don’t you fucking try it with me, boy! I’ll fucking have ya!’ I knew I couldn’t really be that, I was far too wimpy to frighten anybody. It just felt so good to be accepted.

Even when I’d got the other kids at school to stop making fun of my name – now Mike or Ross – and my accent – now cor blimey guvnor – they still found ways to pick on me. They said Italians always stank of garlic and ate worms – spaghetti. So I would put on this tough kid facade. I learned to swear a lot and pretend to be this macho Jack-the-Lad funny guy. Like Alan Lancaster: except he didn’t need to be funny. He was genuinely tough. I had to be funny because that was my best defence, always. But I never felt like I was being myself. I knew it was all just an act. My eldest son, Simon, was somewhat similar when he was growing up, though under different circumstances. Just being hypersensitive. Simon now works in musical theatre and opera – he’s an incredible singer – and he told me that when he finally got into that world he really felt happy, that he had found his true element in which to thrive. What I’ve got, I’ve had to fight for every step of the way. Putting up a front, while secretly peeking out from behind the mask waiting for it to be safe to come out and play – as myself and no one else.

Where we lived in Balham, it was a world apart from Forest Hill, where we’d lived with Nonna. It was rough. Prostitutes didn’t wait for night: they just stood on street corners asking passing motorists if they wanted ‘any business’ in the middle of the afternoon. More than once my mother went outside to try and break up some fight the working girls would be having in our shop doorway. I knew they were ‘bad girls’ but even if you’d explained to me precisely what they did I wouldn’t have really paid much attention. I was eleven when we moved to Balham and though I’d been fiddling around under the blankets for a while, the world of sex was not something I had given a lot of thought to. I didn’t equate playing with myself with having sex with a member of the opposite sex. When some of the older kids in the neighbourhood told me and my mates about some barber in the high street who would give boys a fiver if they let him give them a wank under the barber’s sheet, we all talked about it for a few days.. A wank was just a wank. But being given a fiver – that was a fortune to us back then. We soon came to our senses though. Our brains were catching up with our bodies and going down the barber’s didn’t seem like such a good idea.

Meanwhile, as a teenager I did more or less become part of Alan’s family. For better or worse. The Lancasters were an archetypal hard-as-nails old south London family from Peckham. They had a black cat called Nigger. But they were an amazingly close loving family, and I was so happy to be considered part of it during those years. It made me feel for the first time as if I belonged somewhere other than at home. It made me feel safe. But I look back now and see it as a failing of mine. A real weakness of character that I could be so easily led as a kid, that I was so desperate not to stick out from the crowd. They were good people but they weren’t my people. I was just happy to be allowed to be with them. Not a good foundation for any healthy relationship.

There are lots of areas of my younger life I look back on now and cringe. I’m sure a lot of people do. I think that’s a good thing, because it shows you’re learning as you go, through your mistakes. It’s often the ones that look back on their childhoods and see no mistakes at all that are the ones to watch out for. Rick Parfitt was like that. But Rick was an only child and a lot of only children are like that, in my experience.

Even though Alan was the leader when we were kids and could be very intimidating, he used to like the idea of us being pals and being so different. I was tall and he was short. Years later when we were still trying to get Quo off the ground, Alan showed me a picture of Simon and Garfunkel. He said, ‘Look, that’s you and me, that is.’ One tall blond one; one short dark one. I was like, you’re right! But inside I was thinking: that’s not how I see us at all. But Alan was happy and that’s all I really cared about when I was young, keeping other people happy, so that they wouldn’t take against me. And I could fit in. Didn’t matter into what. Just so long as I wasn’t left outside in the cold.

Chapter Two

Happy Campers

I learned to play guitar by listening to records and trying to play along. First just pop records that I happened to like, then anything and everything. Guy Mitchell, who was my mother’s favourite, I remember trying to play along to. Connie Francis and ‘Everybody’s Somebody’s Fool’ was another one I seemed to pick up easily. Mind you, I had a thing for Connie Francis as a kid and imagined meeting her and bowling her over with my uncanny ability to play her hits. I loved her voice: that catch in it that made it incredibly sexy to a pre-pubescent boy – plus, she was Italian. It was only much later when I looked back I realised I was listening to a sort of pop version of American country. I’ve loved country music ever since.

I was never going to be a virtuoso guitarist. I only ever went for one proper guitar lesson and that was from some dodgy geezer at Len Stiles Music on Lewisham High Street. This was a record shop that also sold musical instruments including electric guitars. Len Stiles was the place where you hung around smoking your Nelson cigarettes and yacking about music. This guy gave lessons there and I thought this must be the place to learn. But when I asked to be shown some Everly Brothers tunes this old fellow looked at me with scorn. ‘We don’t do any of that rubbish here, laddie!’ Calling me ‘laddie’ also put me right off. It sounded so old-fashioned. I walked out never to return. It was two lessons in one: my first and my last!

After that, there was this feeling that even trying to learn an instrument was somehow out-of-date. It didn’t help that all the teachers usually offered were old dance tunes or ballads. I wanted to play the Everlys’ ‘(Till) I Kissed You’, not some old waltz. It seemed like you had to learn on your own if you wanted to learn how to play the modern sounds you heard on the radio. There was a real disconnect in those days between the older and younger generation, particularly when it came to music. The music teachers objected to showing younger players like me how to play such ‘rubbish’ as the Everlys or the Beatles, who I’d also fallen for, just like everyone else in 1962. They were like the Everlys in that they played guitars, had really catchy songs, and this brilliant vocal harmony thing going on, where the voices all sounded like one.

Now there are some smartarses out there who will be sniggering at this info and thinking how this explains the, in their eyes, ‘limited scope’ of Status Quo’s music – the old heads-down-three-chords-no-nonsense-boogie label. And I will concede they might have good reason – up to a point. But while I was never going to be able to play guitar to the same jaw-dropping level as an Eric Clapton or Jeff Beck, I was determined I was going to become a bloody good songwriter. Besides, if you listen properly you’ll discover that whether it’s me playing something relatively straightforward like ‘What You’re Proposing’, which was a huge hit for us in 1980, or Cl

apton on fire in Cream, we are both playing the same bunch of chords. It’s not about how many – or how few – notes you can play or how fast, it’s all about whether the music touches your soul – or your groin.

There are only so many notes and chords you can play on a guitar and it’s all about the way you play them. Which means it’s all about who you are, not what you are. There’s a story I like about the great American guitar player Chet Atkins. Chet could play anything from country to pop and all points between. He was known as Mr Guitar. Well, this story about him might be apocryphal but it says it all really. He was sitting in a chair playing one day, just for fun, in some guitar shop or somewhere. And one of the customers stopped to listen and said to him: ‘My-oh-my, Mr Atkins, that guitar sure does sound pretty.’ Chet looked him over and said, ‘Yeah?’ Then got up, put the guitar back on its stand, and said: ‘How does it sound now?’

The moral being, anyone can pick up and play a guitar. But only you will ever sound like you. And that’s what you aim for. Making the guitar do something that is real to you. Of course, it took me a long time to work that out for myself. But whenever people make jokes about Quo only being a three- or four-chord band, it says more to me about the people saying that than it does about what Quo have achieved as a band.

Anyway, practising the guitar or trying to learn stuff I didn’t actually need to know at the time went right out the window for me the moment I mastered the basic chords. I’m not saying that’s good. These days I practise every single day. But as a kid it probably made me even more single-minded about starting my own band and simply going out there and playing anywhere that would have us.

I Talk Too Much

I Talk Too Much