- Home

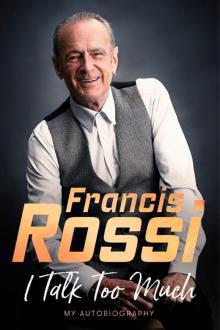

- Francis Rossi

I Talk Too Much

I Talk Too Much Read online

Copyright

Published by Constable

ISBN: 978-1-47213-017-4

All characters and events in this publication, other than those clearly in the public domain, are fictitious and any resemblance to real persons, living or dead, is purely coincidental.

Copyright © Francis Rossi, 2019

The moral right of the author has been asserted.

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, without the prior permission in writing of the publisher.

The publisher is not responsible for websites (or their content) that are not owned by the publisher.

Constable

Little, Brown Book Group

Carmelite House

50 Victoria Embankment

London EC4Y 0DZ

www.littlebrown.co.uk

www.hachette.co.uk

Contents

Copyright

Prologue

Chapter 1: You Talk Funny!

Chapter 2: Happy Campers

Chapter 3: Matchstick Men

Chapter 4: Three Grand Deutsche Car

Chapter 5: Get Down!

Chapter 6: An Offer You Can’t Refuse

Chapter 7: Runny Nosin’

Chapter 8: Twelve O’clock in London

Chapter 9: Army of Two

Chapter 10: Deeper and Down

Chapter 11: Davey Rock It

Chapter 12: The Double Act

Chapter 13: Here We Are and Here We Go

Picture Sections

Prologue

For some people the past is a distant planet. Somewhere they used to live long ago that they can barely even remember now. Somewhere that doesn’t really matter any more, in fact. Not me. For me, the past is always there. A story I can never really stop messing around with, trying to figure out how it all happened. Why it all happened. The past comes back to me any time it wants. Often when I least expect it.

Sometimes, I will be sitting around and something I thought I’d forgotten about, sometimes just the littlest thing, snaps back into my mind and I think, ‘Ah, yeah! Now I get it! So that’s what that was all about …’ Sometimes it’s bigger things, stuff that I just can’t let go, no matter how hard I try, because it still bugs me. Still gets under my skin and makes me want to have a go. Hit back. Put it in its place.

My wife Eileen says it’s because I never stop analysing things. That I go too far sometimes and won’t stop fiddling with something in my brain until I feel like I’ve finally worked out what’s going on. Only to come back to it again days, sometimes weeks, sometimes years later, and start analysing it all over again.

So if there are things in this book that seem contrary to you, that’s fine. There are things in this book that definitely seem contrary to me too. Things I didn’t really know about myself until I started putting down my thoughts. Things that I’m still thinking about, analysing, working out what really went on. Things I’ll probably still be thinking about until the day I die.

Like my relationship with Rick Parfitt: I’m fully aware that now he’s gone, everyone wants to get me to open up and tell them everything about that. But I can’t. Not absolutely everything, once and for all, as if the story’s over. Because it isn’t. Rick was such a huge part of my life for so long – over fifty years – I’m still analysing what really went on there between us. I know what his family thinks. I know what the Status Quo fans think. But what I think about it is something I have to deal with every day, even though he’s not around any more – especially now he’s not around any more – and it changes from moment to moment.

I loved Ricky and I still do. He sent me bonkers a lot of the time and somehow he still manages to do that too. He was everything that I wasn’t and used to wish I could be: flash, good-looking, talented, the glamorous blond – a real rock star, in the truest sense. Someone who lived for today and to hell with tomorrow, love ’em and leave ’em, no encores. Mr Showbiz.

While I was the opposite: an insecure show-off, always overcompensating, thinking about tomorrow. The dark-haired balding one; talented, perhaps, lucky, definitely. But the guy who always made damn sure he looked every gift horse in the mouth and counted every one of its teeth. Then made a note of it. Then counted them again.

They say opposites attract. That when opposites attract and things go well, they go spectacularly well. But that when opposites attract and things don’t go so well they go catastrophically badly. Well, that was certainly the case with Rick and me. When things were good, they were very, very good. But when things were bad …

Anyway, we’ll get to that. The first thing to make clear though is that this is not just a book about my relationship with Rick Parfitt, though obviously a large part of that comes into it. Nor is this especially a book about Status Quo, the group I have fronted for almost all of my life. Though, again, obviously they play a big part in my story too.

This is a book, for better or worse, about me: Francis Dominic Nicholas Michael Rossi. Though Rick always used to call me Frame – because I was so wiry, with chicken arms and legs. There were other names he called me too – when he thought I wasn’t listening. Then there’s the lovely names my wife and kids call me sometimes – to my face!

And then there are the names I call myself, sometimes when I’m alone and brooding – analysing – retracing the steps of a life that, by the time you read this, will be almost seventy years old.

A good time to stop, you might say.

Or an even better time to keep going, I say. Right now, anyway.

Tomorrow might be different.

Mightn’t it?

We’ll see.

Chapter One

You Talk Funny!

The helicopter took off straight from the backstage area of Milton Keynes Bowl and within seconds the 60,000 crowd below looked like ants.

Actually, they had looked like ants to me even when I was onstage. By the time we did the encores, I was so coked I could barely see the guitar in my hands and I’d fallen over several times. I had to be carried offstage at the end by a roadie, who slung me over his shoulder.

All I knew for sure was that I’d never have to do this again. Stand up onstage with Status Quo and pretend to be enjoying myself. It was over. The end of the road.

Bloody hell, what had I done?

That was the question everyone was asking in 1984. Everyone, that is, except me. Like the coke-addled, tequilaguzzling, Mandrax-scoffing, dope-smoking smartarse I was, I was absolutely sure I knew what I was doing. Breaking up the band I had spent over twenty years building into one of the biggest in the world – why not? It was their fault. I was sick of the band, always making demands. How would I manage on my own though? Silly question. I would manage just fine. I would have a successful solo career after leaving the band just like Rod Stewart had done when he left the Faces, wouldn’t I? Or like Ozzy Osbourne had done after he left – got booted out of – Black Sabbath. Wouldn’t I?

Um, well …

Anyway, that was all something I could deal with later. Much later. After I’d finished doing the Quo farewell tour. We billed it as the End of the Road tour, and all the publicity around it was about it being the last time anyone would get to see the band play live. They were almost all big venues, and where they were normal-sized we would double and triple up, doing multiple nights. Shows across Europe followed by forty-two shows in Britain, including a week at the Hammersmith Odeon in London, for which all 28,000 tickets were sold within four hours of going on sale. The finale was to have been a big outdoor show before 25,000 fans at Crystal Palace’s football ground, Selhurst Park, in July. But again, ticket demand was so great we ended up adding one last big

blowout show before 60,000 fans at the National Bowl in Milton Keynes.

I had been told by the record company that the end of Quo was probably going to be the end of my career. I just laughed and had another line of coke. I’d show them! I’d show them all! Ha ha ha!

I was thirty-five but the punk music press had been calling me a has-been since I was in my twenties. I didn’t care. Fuck ’em all! That’s what I told myself when I woke up on the floor each day.

The only one I felt sorry for was Rick. Poor Ricky Parfitt. Drummer Pete Kircher and keyboardist Andy Bown were pragmatic about the band ending. They were session guys who hadn’t been there at the beginning and they would find another gig. Alan Lancaster may have still seen the band as his creation, and I might have thought of myself as the more bankable frontman. But no one loved being in Status Quo more than Rick Parfitt. No one relied on being in Status Quo as much as Rick Parfitt. His whole worldview was tied up in being the brilliant rhythm guitarist, successful hit-writer and good-looking blond singer in Status Quo. And, of course, all his fragile finances were tied up with Status Quo staying together.

I think he thought it was just another jolly PR wheeze, all this announcing the band’s farewell. It wasn’t until the helicopter took off after that final show and he looked out the window that it finally sank in. When he looked over at me, he saw that I really wasn’t kidding. That I was done in, had it, gone.

The truth is, we were both scared. I was too scared to carry on. Rick was too scared to stop. I felt like I had gone as far as I could with Status Quo, with fame and money and expectation and criticism – three-chords-heads-down-blah-blah-blah. Yeah, funny, ha. Rick felt like he still had a long way to go, with fame and money and … what else was there? Bring on the dancing girls!

That had always been the difference between Rick and me. We were like night and day. I only ever saw the darkness. He only ever saw the light. He as Mr Show. Me as Mr Business. Neither one of us had it right though. Not then anyway. Not ever, I realise, now I look back.

Anyway, it was too late to turn back now. The band had been together in one form or another for longer even than the Beatles. Almost as long as the Rolling Stones. I’d had enough. And now it was over. Thank fuck for that.

Until Bob Geldof phoned up one day not long after and asked me and Rick to sing on his Band Aid record. Do what? Never! Status Quo was finished. Never to be seen again.

Typical Bob, he just yelled back at me. ‘I don’t give a fuck about that! Just get back together for the day.’

All right then, Bob, we said. But only for one day …

I was born in Forest Hill, south London, into a large house full of Italians. There was my dad and all his brothers and their wives, then all the grandparents and children. It was all one big family. My dad put an ice-cream van right in front of this lovely house and it pissed off all the neighbours. As soon as we moved in, the area went down. As soon as we moved out, it went back up again.

My mother, Anne, was born in a small coastal town called Crosby, on Liverpool’s Merseyside. Her father was an Irishman named Paddy. According to her family, Liverpool was the capital of Ireland. All her friends called her Nancy. Mum was a Catholic so she was the same religion, but she was always a bit of an outsider to the Italian side of the family, as one of the first of the English wives, although she was always desperate to be thought of as Italian. My father, Dominic Rossi, was born in London but was about as Italian as it is possible to be. His mother – who everyone called Nonna whether they were related or not, including all the van drivers – came from a small Italian town called Atina, famed for its olive oil, red wine and beans. Not a bad combo. We all called our grandpa Pop. His brother was known as Uncle – to save confusion. Don’t ask…

Names were always a funny thing in my family. I was given my dad’s name, Dominic, as my second name and my younger brother has it as his first. I don’t know why. I suppose they must have really liked the name. Before me, though, there had been a daughter, Arselia, who died because of a heart defect. My mother, being Catholic, took a vow that her next child would be named Francis – after St Francis of Assisi – and a few other saints, which is why I have the longest name in the family: Francis Dominic Nicholas Michael Rossi. None of this meant much to me at the time. It was only when I got to school that the name ‘Francis’ presented a problem as the other kids taunted me for having a girl’s name. I tried to fix that by telling everyone my name was really Mike – or just Ross. Frankly, they could – and did – call me anything they liked as long as they left me alone.

Names and relationships were all very tangled in my family. In truth, I never quite figured out what relationship everyone was to each other. Nonna – my grandmother – was a Coppola, which I’ve been told is very good Italian stock. What’s funny though is that when I looked the name up on one of those ancestry websites the following information popped up: In 1881, the most common Coppola occupation in the UK was Ice Cream Dealer. 100% of Coppolas were Ice Cream Dealers.

Guess what my dad’s family all did for a living – that’s right, selling ice cream! Apart from the ice-cream vans, they owned a shop on Catford Broadway called Rossi’s Ice Cream. He was always trying to think of ways to bring in extra money. In the evenings, instead of ice cream, my dad would go out in the van and sell fish and chips. The last time I checked, the family still owned the shop and were now renting it out as a betting shop. I was born on a Sunday – on 29 May 1949. According to the modern version of the old nursery rhyme, Sunday’s child is ‘happy and wise’. Yes, well, they got that wrong. On the other hand, according to the original text from The Oxford Dictionary of Nursery Rhymes, ‘And the child that is born on the Sabbath day/Is bonny and blithe, and good and gay.’ Which doesn’t sound right to me either.

At the time I came along we all lived in my grandma’s large house in Mayow Road, Forest Hill, because my parents couldn’t afford their own place. Pop – my grandfather, do try and keep up! – left all the ice-cream business to Nonna. By trade, he was a parquet-floor layer. As a teenager, my dad had been his apprentice. Then he nearly lost his hand in an accident at work. He’d told his younger brother Chas to drive the car to a job up north. Fine except for the fact that Chas hadn’t actually passed his driving test. Which explained how he managed to drive across the street and straight into a bus.

My dad flew straight through the window and hit the road just in time for the bus to drive over his hand. They were still picking up bits of his hand when the ambulance arrived. Poor sod ended up having more than forty operations to try and save the hand. When my mum took me to visit him in the hospital I nearly fainted – they had sewn his hand inside his stomach to help it heal. That’s what they told my mum anyway. He ended up with a deformed sort of claw for a hand. I didn’t mind. Kids take things in their stride. He used to wave it at us kids and pretend to be a monster. We’d all run off laughing. It wasn’t until many years later it dawned on me that he was very self-conscious about it. He didn’t like it if people noticed it and wouldn’t let his grandchildren see it at all.

When we moved from there a few years later to this sweetshop a few miles away in Balham, my dad still kept the ice-cream van going. When one of my uncles died, I heard my dad and all the other men talking at the funeral about how they were going to have to divvy up the remaining ice-cream routes. Business and family was one and the same thing to them. I was too young to know other families – English families – did things differently. By the time I’d figured it out it was too late and I was like that too. Work and family, that’s all I’ve ever known. Evenings for me as a kid mainly revolved around sitting with my dad and his brothers listening to them tell stories about their day. How many cones they had sold. Who had had a good day out there in the vans and who hadn’t.

These days, people talk about having a ‘strong work ethic’, and you could say I have one. But I just didn’t know any different. Apart from going to church on Sundays – and even then it was straight back

to work for my father on the ice-cream vans – we didn’t really have what you would call ‘days off’. Working evenings and weekends was just normal to me. I think this must have affected my attitude later when I became involved in trying to make it in a band. Strange hours, working on those days and nights when so-called normal people were relaxing, never worrying about things like holidays, putting every spare penny back into the running of the business, or in my case keeping the show on the road, none of this was a sacrifice to me. It was just the way I’d been brought up. People talk about rock musicians being like kids in a sweetshop: well, I was that kid in a sweetshop, and it never meant anything to me. The sweets were always there for selling. Sure, I would enjoy the fruits of my labour, but I still got out of bed the next day ready to work. I see now that this all came from my childhood.

As a result of this mixed bag of Italian-Irish-northern-cockney influences, I grew up with a very mangled accent. It was the same for my brother and our two cousins. Not that I noticed I had an accent, or at least not until people like Quo’s Alan Lancaster pointed it out. From my mother came this mainly northern accent. You can hear it on ‘Paper Plane’ and some of the earlier Quo tracks. Dig out ‘I (Who Have Nothing)’ on YouTube from when we were still the Spectres and I sound completely Lancastrian! Plus, we were all listening to the Beatles and that’s how they sounded when they sang.

From my dad I had this Italian-cockney thing going on. Because we spoke a lot of Italian at home but outside the home they wanted to be English, we spoke-a-like-a-this-a. And like-a-that-a. There was always a vowel on the end of every sentence. I spoke Italian most of the time until I was about seven but it got less and less as I grew older. I can remember going on holiday with my family to Italy when I was about five or six, playing with my cousins and speaking to them. In my memory we are speaking English because we understand each other perfectly. But in reality, I realise now, it was because we were all speaking Italian.

I Talk Too Much

I Talk Too Much