- Home

- Francis Rossi

I Talk Too Much Page 4

I Talk Too Much Read online

Page 4

By the time I met Alan Lancaster I was into the ‘heavy’ stuff. That is, all the American rock and rollers like Jerry Lee Lewis, who used to frighten the hell out of me, and all the other wild and crazy singers like Little Richard, Eddie Cochran, Gene Vincent, Chuck Berry … I’d also discovered Buddy Holly by then, who was similar to the Everly Brothers, except even more exceptional in that he had this really exciting take. The hiccupping voice, that great band he had behind him. Those songs, the best of which he wrote himself … And he wore glasses and was not the typical good-looking pop star. Like a lot of other aspiring young British musicians of the time, I thought, if he can do it then there’s a chance for all of us.

Alan and I were still in the school orchestra playing our brass instruments when he and the other Alan – Key – started talking about having a little beat group outside school. Alan Key’s older brother was in Rolf Harris’s backing group, who’d had big hits with ‘Tie Me Kangaroo Down, Sport’ and ‘Sun Arise’, which was a really big deal at the time. He would let Alan Key use his spare Fender Stratocaster, which I was very envious of. We had another mate from school, Jess Jaworski, playing keyboards, and Alan Lancaster on bass. He had somehow managed to get his parents to fork out for a blond Höfner bass. I was amazed – and impressed. It was a beautiful-looking instrument, but he couldn’t afford a guitar case so he used to carry it around in an old plastic shopping bag.

Our drummer was a lad called Barry. I can only remember his first name, which he will hate me for, but he probably already hates me anyway – I’ll explain in a moment. That left me on guitar, which was fine while we were just mucking around playing Shadows instrumentals like ‘Apache’ and ‘Kon-Tiki’. Not that I could manage to play like Hank Marvin. I was far too lazy to learn that – most of the lead instrumental work was done by Jess on the keyboards. But then the rest of the band wanted a singer – and decided that it would have to be me. This was not something I had bargained for. It was one thing to know all the words to ‘Wake Up Little Susie’ or ‘Love Me Do’, quite another to get up on a stage and sing them for an audience. But it was made pretty clear that if I didn’t do it they would look for someone else who would. So I held my breath and jumped in at the deep end. And … it seemed to work. I think I sang ‘Michael (Row The Boat Ashore)’. Well, we made such a noise you couldn’t really hear the vocals that well, so I was safe for the moment. That’s how I looked at it.

The singing malarkey had begun when we were playing in the school orchestra. We were basically modelling ourselves on Kenny Ball and His Jazzmen, a modern trad band from Essex who had quite a few hits in the early sixties, led by trumpeter Kenny Ball, who would set aside the trumpet here and there to warble a few vocals. We would do one of Kenny’s big hits, ‘When the Saints Go Marching In’.

But it was all just school stuff, we knew that. Singing while playing guitar in a group, that was another level, but I smile about that now because the fact is I’m pretty sure we never actually got around to playing any gigs. We would just rehearse in Jess’s bedroom. The group was named the Scorpions. But then Alan Key, who ironically was the one who really pushed for the group to happen, decided to leave. He announced that he planned to marry his girlfriend – who was, literally, the girl next-door to where he lived – as soon they reached sixteen, and that he thought it best if he stepped down from the group now to allow us time to get someone new in. Alan was lovely like that, always nice and thoughtful. Far too nice, you might say, to be a working musician.

Stepping down was a very noble thing for a fourteen-year-old to do, and very generous and forward thinking. As I discovered later, most young guys in groups sooner or later faced the choice of settling down with someone or giving everything up to try and make it as a musician. Most of them leave it too late to decide, though, and this either lumbers the group they are in or completely messes up their relationship. In my case, it would be the latter. Alan Key, however, somehow foresaw this and did the right thing. His reward is that he’s still with the girl of his teenage dreams all these years later – and I’m still in the group. But then it never felt to me like I went from some safe sort of home environment where a so-called normal life was mapped out for me. School, job, wife, kids, death. For the Rossi family, school was what we learned at home; jobs was what we did at home; wives were meant to fit in with that or not at all; kids were for wives; and death was something that was never going to happen to me, thank you very much!

This is when John Coghlan came into the story. Not to replace Alan Key, but to take over from Barry. It was a bit complicated but the short version is that Barry’s dad had wangled us a proper place to rehearse, which was this old garage in Lordship Lane, Dulwich. It was next-door to the south London headquarters of the Air Training Corps (ATC). All the air cadets went there, which is how we met John, who was one of the cadets. We had only been in the place a few weeks when we discovered that the air cadets had their own group that also used to rehearse there. They were called – wait for it – the Cadets. One night we walked over to check them out. They were all a little bit older than us and although they hadn’t done many gigs either, it was obvious they were streets ahead of us at that stage – especially the drummer.

That got us plotting. Barry was a good bloke but a pretty average drummer. Hardly surprising: he was only a kid, like us. But John was on another level as a drummer. The difference was really noticeable. You can fake it a fair amount if you’re not that good at guitar or bass, but drums are so important in a group and you’ve either really got it or you don’t. I have to confess, though, there was another reason why not having Barry around any more suited me. I was ‘seeing’ his girlfriend. How I remember it, she was the one that instigated it. She was bigger than me and used to getting what she wanted. I’m not saying she held a gun to my head, but the first time she went to give me a blowjob I couldn’t understand why she kept moving her head down there. The truth is I didn’t know what she was trying to do – put my knob in her mouth? Bloody hell! Whatever will they think of next?

When the whole thing came up about stealing John for our group, I didn’t say anything to the others but it’s fair to say I was relieved. That’s a group for you: selfish to the bone. I was going to say ‘young groups’, but actually it’s groups of any age. You always want to get better at the music – and get your willy seen to. Sorry, Barry. But you’d have probably done the same.

So we brought John in and he was amazing – his playing really took us into another league musically. We were now the Spectres and John joining on drums was the moment where we started to take things seriously. He had already left school; he’d been at another comprehensive called Kingsdale, which was in Dulwich. He was also three years older than the rest of us, and an air cadet, which also lent him an air of authority. Though not to Alan Lancaster, of course, who would take on anybody, no matter how old – and win, usually. Most importantly, John Coghlan was already what you would call a ‘proper’ drummer. He’d taken lessons from someone called Lloyd Ryan, who really was a ‘proper’ drummer, having played with people like Matt Monro and Gene Vincent. Ryan was an amazing character who would go on to play with all sorts of sixties stars like P. J. Proby, the New Seekers, Tony Christie … He also, rather wonderfully if a little bizarrely, went on to become the manager and chief spokesman for the masked wrestler, Kendo Nagasaki.

We knew we’d moved up a gear the day John arrived for his rehearsal with us. He turned up in a minicab. Minicabs were still a new concept in 1962 and we all thought he’d been chauffeured! Later, John levelled with us, saying his dad had told him: ‘Make it look good, son.’

Thankfully, John used to be the most un-flash sort of guy you could hope to meet. For a drummer – they are mostly mad – John was quite quiet. Except for those times when he wasn’t. Times when he got the hump about something and literally just exploded. John wasn’t much of a joiner-in, let’s put it that way. He kept himself to himself, didn’t feel obliged to pretend to be anything he

wasn’t, and just got on with his drums. The main thing was, John was a good drummer – and he knew he was a good drummer. The rest of us were still hoping to be good one day. This is where Alan Lancaster’s sheer bloody-mindedness came in handy.

It was this line-up – me, Alan Lancaster, John Coghlan on drums and Jess Jaworski on keyboards – that began working properly as the Spectres. Alan’s dad had arranged for us to play a regular weekly show at the Samuel Jones Sports Club. My dad would pack our equipment in the back of his ice-cream van and drive us. There wasn’t much of a turnout, just family, really, and a few mates. But I would not allow the group to start playing until Alan’s mum got there. Her approval meant so much to me. Once we started, we would do a few covers – instrumentals and chart stuff – then do a runner after about half an hour. It forced us to become professional – or semiprofessional. It was hard for a bunch of school kids, and also for John, who had left school behind when he was fifteen and was throwing in his lot with us. It would have been easy just to let the whole thing fizzle out.

This went on until one night this bloke came up to us after we’d finished and uttered the immortal words: ‘I want to manage you.’ To us, this sounded like ‘I want to make you stars.’ Because we didn’t know what a ‘manager’ actually did. We thought he would just give us money and get us on the telly. Or something. We didn’t know what he would do. We just said, ‘You’ll have to ask Alan’s mum.’ So May gave him the once-over, decided he’d probably be all right and suddenly the Spectres had a manager. Whoopee!

Our new manager’s name was Pat Barlow and as it happened he had zero experience of the music business. He was a gas fitter who had done all right for himself, to the point where he now ran his own gas showroom. He wasn’t a big cheese with millions at his disposal, but he was ‘flush’, as we would say. He’d made some money and now fancied, as he put it, ‘getting into this pop music game’. Why not? The Beatles were enjoying their first hit singles. The Rolling Stones hadn’t released a record yet, neither had the Kinks or the Who, yet there was this feeling suddenly, especially in London, where you could just make something happen simply because you were young and ‘with it’. Or maybe all teenagers feel like that when they are making their first steps beyond school.

Either way, Pat Barlow fancied having a go at turning the Spectres into the next Shadows, maybe even the Beatles. Or at the very least, turning a profit. The important thing is Pat began beavering away for us and the gigs began rolling in. He may not have known anything about the music business but he had the gift of the blarney and he never gave up. He would get on the phone and not get off again until he’d dug up something for his ‘boys’. Now we were playing places like the El Partido club in Lewisham, which became a well-known mod club. Pat also got us a Monday-night residency at the Café des Artistes in Chelsea. Even though most of us were still at school, we’d be playing there until the early hours of the morning. Our parents all knew Pat would be there to look after us, though, and drive us all home afterwards, so they were fine with it. Pat was like another parent to us. One time when my hair had gotten quite long – well, long for those days, which meant it had grown past my shirt collar – Pat grabbed me by the neck and cut off about six inches of hair from the back with a pair of scissors. I put up with it though because I was still a schoolboy and he was a grown-up. In those days, neighbours were allowed to give you a clip round the ear if they thought you were being unruly and your parents wouldn’t say a thing.

We trusted him and so did our families – especially when some money started coming in. My mum and dad might not have fully understood the sort of music we were into but they totally got what was going on when they saw it bringing in money.

Overnight, our equipment got better. I was able to buy a new Guild semi-acoustic guitar. Alan splashed out on a smart new Burns bass guitar. And we started getting into clothes – clobber. At first, that meant wanting to look like the Beatles, all in the same blue suits. It was just the way all the pop groups dressed in the early to mid-sixties. There was this fella down in Lambeth who would tailor-make them for us at £12 a go. Alan decided he needed a more special kind of suit – he still saw himself as the leader and he felt he needed something to mark him out as such – and so he paid £25 for his. Watching us onstage, you couldn’t tell the difference – they were all the same shade of blue. But in Alan’s mind his suit was just a little bit better and that kept him happy.

In our own way, we were all becoming a little bit cockier, I suppose. The next logical step was to get a record out but none of us had the faintest idea how to go about making that miracle work. Even Pat couldn’t sweet talk any record company people into delving into the deep south of London to come and see us play. This went on for months and months until Pat had the bright idea of trying to get us onto the bill with one of the groups that the record company crowd would definitely turn up for. But again, easier said than done.

Then, sometime towards the end of 1964, Pat saw an advert for the Hollies, who were playing at the Orpington Civic Hall in Kent, and decided to try and blag us onto the bill as an opening act. How he managed I don’t know but somehow Pat pulled it off and, sure enough, by the time we took the stage in Orpington, sometime early in 1965, we were convinced that this was our big break. That the place was packed with leading music-biz impresarios just dying to sign this hot new group they had heard so much about.

We were dreaming, of course. I have no idea if there was anyone at all from the biz there that night but by the end of it I was praying there wasn’t. We were awful. We were so crippled by nerves we could hardly stand up straight, let alone play and sing. The whole thing felt like a giant setback. I thought: that’s it, we’ve blown it now. But I was fifteen. I hadn’t come even halfway to blowing it yet. That was something I’d be much more successful at later, once we were famous.

Our real big break, not that we saw it quite that way at the time, was when Pat excelled himself and got us an audition for a summer season booking at Butlin’s Holiday Camp in Minehead, Somerset. Now this was genuinely exciting stuff. Half a century later Butlin’s is still a good affordable holiday spot for families with young kids, or older relatives. Back in 1965, though, it was like Britain’s answer to Las Vegas. Until Butlin’s came along, a typical working-class family holiday was a week at a bed-and-breakfast by the sea, the sort of places that were usually a few spare rooms in someone’s house, which you were locked out of all day. Butlin’s came along and suddenly Britain had actual ‘resorts’. Places where the kids could play at the fair all day and the adults could grab a drink and put their feet up at night. For teenagers, Butlin’s also offered the previously unknown pleasures of living away from home for months at a time, getting all your meals provided and chasing as many pretty girls as you could find. And you didn’t have to look very hard, obviously.

The first few nights we played there as the Spectres I thought I’d died and gone to heaven. The Butlin’s holiday camp in Minehead had only just opened a couple of years before and was the newest and most ‘glamorous’ of the various camps around the country. The day we arrived was genuinely momentous for me. It was my sixteenth birthday, and who happened to be at the check-in centre at the very same moment we arrived but the guy who was to become my lifelong musical partner, Rick Parfitt, and my future wife, Jean Smith! Not that I knew any of that yet, obviously.

Being part of the ‘nightly entertainment’ meant we got a lot of attention. It was my first summer after leaving school, too, so the whole thing was like a rite of passage for me. That might sound pretentious but I can’t overstate what a big step up the Butlin’s gig was for us.

In fact, once we had left school, Jess Jaworski decided he’d had enough of late nights and an uncertain income, and decided to stay on at school and take his A levels. This is another make-or-break moment for any aspiring young musician. You can only survive on dreams for so long. If you haven’t made it after a certain time, it seems only sensible to throw in the towel

and get a regular job like everybody else. But this Butlin’s booking definitely represented a turning point for the group and Jess rightly recognised that. For Jess, it was time to be thinking about things like apprenticeships or college and solid offers of paid employment. For some aspiring musos the big decision to pack it in comes at thirty or thirty-five. Some never give up the dream and find jobs that allow them to keep playing at weekends and what have you. Jess saved himself – and us – a lot of unnecessary grief by making his decision early and good on him for doing it.

The guy Pat managed to find to replace Jess on keyboards was Roy Lynes. Roy was even more laidback than Alan Key and even older than John Coghlan. Alan Lancaster and I were both sixteen when Roy joined and he was about twenty-two: a pretty big gap at that age but what a lovely fella – and a great keyboardist too. Until then he’d been a full-time inspector at a car-parts factory. But he had his own equipment, could really play and slotted right in, in time for Butlin’s. We used to joke that it was Roy’s organ playing that covered up all the mistakes Alan and I made on the guitars.

The novelty of playing at Butlin’s soon wore off, once we realised what a treadmill we were on. We had an afternoon slot, in which we were expected to keep the punters entertained for up to three hours. Then a repeat set the same evening, at the end of which we barely had enough energy to crawl into bed, let alone spend the rest of the night chasing dolly birds, as they were charmingly known. We found ourselves playing over fifty songs a set – twice a day, six days and nights a week. By the third week we had turned into zombies, virtually playing in our sleep. I was practically eating packets of throat sweets for breakfast, my voice was so raw. But that was when we became hardened pros. With that sort of workload, you either gave up quite quickly and went home or you dug down and sucked it up. Well, we weren’t going home, no way. In the end, it made us strong as individuals and really tight as a musical unit. By the time we returned to London at the end of the summer season we were completely transformed. No gig would ever be too daunting again. We were still boys but we were now boys that could look after themselves. We were pros. Lived it, breathed it. Hardened, roughed up, no longer virgins. In any sense …

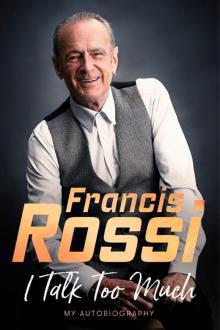

I Talk Too Much

I Talk Too Much