- Home

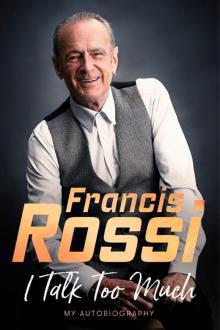

- Francis Rossi

I Talk Too Much Page 2

I Talk Too Much Read online

Page 2

Going to school was what finally killed it off. For a while I would speak-a-like-a-this-a at school and proper Italian when I got home. But that quickly turned into what it is now. It had to in order for me to survive in south London in the fifties. Looking back now, though, I really regret that I can’t speak Italian any more. Travelling the world as much as I have done all my life, and discovering that almost everybody speaks English, it makes me feel slightly ashamed that I can only speak that and nothing else.

As a kid, though, it was all about fitting in. And it wasn’t just my accent I had to worry about. I was what used to be called ‘sickly’ as a child. Always coming down with something. Skinny, runny nose, always getting into scrapes. Tripping over my own shadow. My mother used to say to me, ‘You had such a big head when you were a kid.’ It’s true. I used to fall down the stairs sometimes because my head was too big. I hadn’t grown into it properly yet. Some people say I still haven’t.

I was always falling over and hurting myself. My brother and I – just in shorts, no shirts – ran round this corner one summer’s day and I fell smack on my face. I looked up and there was Mother Agatha – one of the nuns from the Catholic school that we went to, Our Lady & St Philip Neri in Forest Hill. I quite liked her but she stood there staring at me with this look on her face. When we got back to school the next day she did this whole thing about wicked young men running around half-naked. It must have had quite an effect on me, remembering it now.

Something that left an even bigger impression also involved getting hurt in the street. Where we lived on Perry Rise in Forest Hill, when I was about five years old, I walked to school. I used to skip along, quite a happy little chappy. Then one day I was walking to school and saw this kid coming down the street towards me. As we passed each other he hit me around the face with his plimsoll. He hit me so hard with it he nearly took my head off! After that I was scared to go out on my own. They used to send my cousin with me because I was frightened to walk to school. I realise now that this affected me for years after. I didn’t like going out, I was always frightened of people and getting hurt. That said, the fights I have had, I didn’t feel anything. That’s probably down to the sheer adrenalin – the fear. Either way, I don’t like fighting. I don’t like the fire it unleashes in people.

It took me years to analyse what had happened to me though. I was probably all the way into my forties before it finally dawned on me – that my fear of people all began with being attacked on the street by that kid when I was still at school. I decided that I had probably ‘looked at him funny’ on a previous day going to school. Not intentionally, just in that wide-eyed way you do when you’re five or six years old. And that I’d probably frightened him. So he went home that day and told his dad there was this kid down the street who had frightened him, and his dad’s done that dreadful thing dads do sometimes, where he’s told his son: ‘Just go up to him next time, son, hit him as hard as you can – and run!’ Because it later occurred to me that was what he did after hitting me – he ran. He was frightened shitless! So the result was that two kids went away traumatised by that incident – in my case, for the rest of my life. I’m still frightened about most things because of that one moment from my childhood.

It’s odd because I know when people see me on telly or on stage they think of me as super confident, a bit of a know-all, perhaps. But it’s all a disguise. I’m actually always in fear of things becoming out of control. I’m in fear of people. It’s hidden away in some of my best-known lyrics and it’s probably one of the reasons why I got so lost in drugs for so many years. And it’s there now in my insistence on a strict daily routine. Some people call it over-thinking things. Others say it’s about being a control freak. No, it’s just simple fear of the unknown – or rather, the sudden and unexpected. I always expect – and fear – the unexpected. That’s why whenever I’m presented with a new idea, my first reaction is almost always: no. Then, later, much to everyone’s annoyance, including my own, I might be coaxed into changing my mind. You’ll see that happens a lot as you go further in the book.

My wife Eileen isn’t so sure this is all down to one kid hitting me. Status Quo PA and my good friend Lyane Ngan argues with me about it. But I know I’m right. I mean, I hate it when people say, ‘I know I’m right.’ But in this case, I know I’m right. (Smartarse.) That doesn’t mean I’m never wrong. It’s only when you discover just how wrong you’ve been about things sometimes that you learn anything valuable about yourself and the world. And what’s wrong one day might be right the next. We live in the realm of relativity. So you can never be absolute about anything, really, can you? But about this kid hitting me I’m absolutely certain.

Once on the tour bus, Rick, Quo keyboardist Andrew Bown, Dave Salt, our old tour manager, and I were reminiscing about school. Andy was saying how all he ever wanted to do back then was draw. I was saying how I’d love to go back in time and learn more, because I missed so much of it at the time through always being ill. And Rick said, ‘Fuck all that. I know all I need to know.’ Such a sweeping statement! I know all I need to know. How do you know that? And if it’s true, how dull must the rest of your life be? You know all you need to know so you never want to learn anything new ever again? But Rick was like that. Full steam ahead, no looking back. You might as well throw the towel in then and give up. I’m trying to learn all the time. Yes, many things once you learn about them, you’ve cracked it. But there’s always something or someone else ready to come along and teach you something more, something different.

This might also have something to do with the fact that I did most of my learning on the hoof, through experience. Because I missed so much of school I was never going to be an educated kid. These days the school would have held me back. ‘The silly sod hasn’t learned anything. He hasn’t been here!’ But back then because I grew up in retail, it was less of an issue. Everyone just assumed I was destined to go out and sell. I was talking to my brother Dominic about this recently. We were both the same. We grew up knowing we would have to go out into the world and make money through selling, either in a shop, or off a van like my mum and dad, or some other way.

Kids that went to university back then, they were a type of person. I’m not knocking them. They were thirsting for knowledge. Subsequently, it’s become a badge that people wear. My kids have got it. But when the youngest one, who is studying psychology, said to us, ‘I’m not quite sure about this,’ I thought, ‘Good lad!’ My attitude is, no matter how well or badly you were educated, you should never stop learning. Going to university doesn’t guarantee that, though. I’ve met a lot of very stupid people that went and a lot of very smart people that didn’t. And vice versa. The rule is there are no rules. These days, my wife’s friends are like the League of Nations. There are Australians, Americans, Kiwis, Thais, Japanese, a couple of Indians, Irish and an Iranian. I have said to some of them in the past, ‘Why are you so keen for your kids to go to university?’ They say, ‘To get a good job.’ I say, ‘Not just to be happy?’ By ‘good job’, of course, they mean money. Meaning a nice car, a nice house and all that stuff. Yet that was all frowned on when I was a teenager, under the banner of materialism.

I just wish I’d known all this when I was a kid. Instead, for much of it, I felt like an outsider, an oddball. I’m sure a lot of people felt like that at school. For me, it was partly to do with my ‘strange’ accent, slightly northern, slightly Italian, slightly cockney. I lost count of the number of times I got told as a kid I had a ‘poncey’ accent. How they worked that out, I don’t know. But then a lot of other kids thought we were rich, or at least very well off. So did the guys in the band, in fact, when we first started playing together as teenagers. Somehow people always just assumed that I had money. But we didn’t live in a mansion. We lived in a nice house. My mum and dad aspired to own their own property because that’s what retailers did, but we weren’t rich. Other kids from school would come to the sweetshop we had in Balham and go, ‘Wow!

All them free sweets!’ I’d go, ‘Where?’ I didn’t know what they meant. For us kids there weren’t any free sweets. They were shop sweets that my mum and dad sold to customers for our bread and butter.

Even the Catholic Church thought my dad was the bloke to go to for handouts. He ended up supplying free ice cream for the church summer fete, so they could keep the money for their good works. But we were brought up Catholics so we did the whole thing. Holy Communion, confirmation, confession … once you’re indoctrinated with that at two or three years old it’s almost impossible not to go to church for the rest of your life. Though in later life, I’ve succeeded. But it’s been back and forth all my life. You see so many people that went through the same thing, managed to get away from it then have it all kick in again once they have got children. Boys and girls always had their first Holy Communion separately, but I had tonsillitis – again; I had it a lot as a kid – and missed my first Communion date so I had mine with the girls from a convent school. Freud would probably say that was when Catholicism and fun with girls first became intertwined in my mind. And Freud would be right.

For anybody who is religious, let me just say: I have no problem believing in an all-knowing, all-seeing, all-loving, all-powerful supreme being. I say ‘supreme being’ because I don’t want to pick one out that alienates everyone else. I’d be happy with ‘a higher reality’, or ‘the universe’, or ‘energy’, ‘life itself’ – all fine by me. You can find the truth anywhere. Even Catholicism has good points – the importance of family, the dignity of work, taking responsibility for your actions, just basic good vs evil stuff. But what’s the rest of the shit for, Catholic or otherwise? ‘Don’t you touch that! You’re a dirty boy!’ You know what, you’re wrong. Touching yourself is lovely. We lie to kids straight from the off, telling them these things are bad or wrong and go against God. But deep down inside they know you’re wrong. So when you go out of the room they’re going to play anyway. Only now they feel guilty about it afterwards.

My mum was very religious, being a good Catholic girl, and therefore extremely adept at making the rest of us feel guilty if we didn’t go to church. She actually believed I was an immaculate conception and told me so forcefully many times. Hence being named after St Francis of Assisi. As I got older and found the courage, I would challenge her and say, ‘If I’m an immaculate conception, what is my brother then, the dirty one? And how did my dad feel about that anyway?’ She hated that. Blasphemy! Most of the time, though, she was a lovely, fairly normal sort of mum. It all changed when I was nineteen and she underwent this sudden massive religious conversion-cum-breakdown. At which point she informed my brother and me: ‘I’m not your mum. I’m Annie.’ I took it all in my stride at the time, but grew very upset about it as time went on, as I realised I’d suddenly lost my mum. But that’s all for later.

My dad was a lovely man. Born in London but very much still an Italian. Or Italian-cockney. He used to go around saying, ‘Arseholes!’ when things didn’t go right. But in that lovely Anglo-Italian voice, ‘Arsssols! Bluddy arsssols!’ I used to love being with him. He was always going off to work, that was the trouble. So I didn’t get to spend as much time with him as I would have liked. It was great when it snowed or rained because then he would have to stay home. I was very like that with my first three kids, because I was still in my twenties and like my dad always having to go out on the road for work – only in my case I didn’t come home at all for weeks and months at a time. It’s the same for everyone in show business. I didn’t mind at the time, but looking back I see the pattern. Any excuse to get out of the house and away from all the domestics. Later, as a much older dad, with more time spent at home, it was different. I loved being with my kids. It wasn’t until I was already middle-aged and my mum and dad had divorced that I got to know my own dad a little better. He was a lovely man, loved music, very proud of me. I remember playing him that Shania Twain record, ‘You’re Still The One’, and he practically got his willy out, he’d be in ecstasy. I’m the same whenever I really love a piece of music. Bluddy arsssols!

Because of my mum, I used to go to church every Sunday as a child. Then stopped when Quo took off when I was in my early twenties. Then started again a few years later. Then stopped, then started again. You could say writing and making music is an act of creation and tie it in with God. I wouldn’t necessarily put it that way, though. I don’t create religious music. But I do go into a kind of ecstasy when I’m listening to really great music sometimes. I can cry.

In my forties I found myself going to Sunday mass at my local church, John the Baptist, in Purley. I even had my own kids confirmed into the Church, that’s how confused I still was by the whole thing. I ended up in church one Sunday with Eileen when it finally hit me that I just didn’t believe in it any more. I looked around and thought: if there were anything really genuine going on here the kids would be riveted. Kids have those antennae. They can’t help it. Anything going on, they know about it even if they don’t know exactly what it is, they just know something interesting is happening. But they weren’t interested at all. The opposite. You could see by their faces. They were thinking: can we go yet?

One really lovely thing my childhood did leave me with was my love of winter. I love it when it’s grey and cold, because whenever the weather was bad my dad wouldn’t go out in the ice-cream van. My dad was the king of just being. You know, they don’t call us human doings: it’s human beings. And my dad could just be. He was never bored by having nothing to do. For him it was a luxury. He could just be. He was brilliant at it. So as a kid I loved having him around the house. If I looked out the window and it was snowing I’d be so happy because I knew my dad would be in the house all day just hanging around being happy. He’d still be going round the house doing odd jobs but at least he’d be home. I used to dread the summer because I’d never see him. He’d be out all day and night in the van, working. So even now I dread the summer coming – plus it gets too hot and I just don’t like it. I prefer to be indoors, rain lashing against the window, drawbridge up.

I told my dad all this before he died and he amazed me by saying, ‘I hated going out, too, son. I loved being at home with your mum.’ He used to get up and drive to my grandmother’s place in Catford early, 6.30 every morning. Go and load up, get in the ice-cream van and come back home for about 9.30 a.m. Have a wash and brush up. Then he’d come downstairs and have something to eat with my mum. Then be ready to go on his rounds. Do the schools. The playgrounds: all the streets where kids might be out playing. He said that my mum would often try to stop him going, standing there in her baby-doll nightie. He told me: ‘She was a good girl. She knew how to get her own way.’ I was listening to this, not quite knowing how to react. I said, ‘Really?’ He beamed and said, ‘Yeah!’

But that was my dad, full of life. People used to think he’d been on the booze because he was always so up. But the truth is he never touched a drop. It sounds simplistic to say but my talent for showing off on a stage must have come from my dad. That delight in making other people happy. My mother was different. She had a lot of friends, people that loved her. But there was definitely a streak of Irish melancholy there too. A weird uptightness that came to the fore as she got older – and more religious. She would break down. These days they’d have offered her all kinds of different medicines and therapies. But this seemed to be just part of who she was. Maybe that’s where I get my own propensity for gloom from: I’m the most positive person in the world one minute – then the world’s biggest worrier the next. Either that or the drugs. Maybe both …

The truth is, when I look back on myself now as a youngster, I think: oh, what a dickhead! I was trying to follow things, people, trying to fit in. That’s when I met Alan Lancaster. We were the same age and at Sedgehill Comprehensive School in Beckenham. Sedgehill was tough. All the kids from the local council estates went there and it was all about how hard you were. Anyone seen to actually be enjoying lessons was looked down on and tre

ated accordingly. There were kids getting their heads kicked in every day. I liked learning but I did not want to have my head kicked in. So I developed a hard-nut exterior, and being mates with Alan really helped with this as he was the genuine article.

Mainly, I was obsessed with pop music, especially the Everly Brothers. I loved the sound, the songs, and I loved the look of the guitars. Alan was more into Del Shannon, the Shadows and Nat King Cole. Most of the other boys at school were into sport, mainly football. I didn’t like football, which Italians traditionally are really good at. Our sports master at school was a nutcase, yelling at us to ‘Get stuck in!’ and ‘Hack him down, boy!’ What a turn-off. To this day, whenever the rest of the band start going on about football I completely lose interest. (So does Andrew Bown.) I tried rugby and it was a complete non-starter. The pitch was frozen and so was I, and I ended up getting knocked all over the place. Horrible.

I later discovered that there are a lot of musicians like that. They weren’t sporty so they retreated to their bedrooms and sat there practising guitar. People like Pete Townshend and Jimmy Page, Eric Clapton and David Bowie. In my case, it wasn’t just that I didn’t like sport. Outside of music, and watching a few films and reading a few comics, I really didn’t have anything else to connect to. We used to have one of those big old beige Bush wirelesses with the handy handle and lit-up dial. Tuned into Radio Luxembourg. There was something very modern about that radio, almost futuristic too. I would sit there nodding along to whatever pop song it was playing.

There were hardly any songs on the wireless I didn’t like in those days but the ones that really stuck out were things like ‘Red River Rock’ by Johnny and the Hurricanes and ‘The Young Ones’ by Cliff Richard. Cliff’s record had the same eerie effect on me that something like ‘Stairway To Heaven’ would have on a generation of Led Zeppelin fans years later. It felt profound, wise beyond its years, especially the pay-off: ‘Cos we may not/Be the young ones/Very long …’ Even as a twelve-year-old schoolboy, that one would have me almost weeping with nostalgia.

I Talk Too Much

I Talk Too Much